Writers Roger McKenzie (158-166) & Frank Miller (168-191), pencillers Frank Miller (158-184, 191) & Klaus Janson (185-190), inker Klaus Janson, colourists Glynis Wein (158-178) & Klaus Janson (179-191)

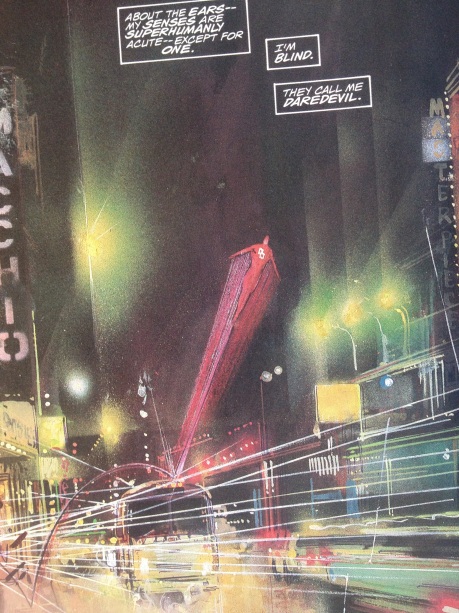

In a bright orange and jagged-edged box in the bottom left corner of the opening page of Daredevil 158 is written: “From time to time a truly great new artist will explode upon the scene like a bombshell! [We] confidently predict newcomer, lanky Frank Miller, is just such an artist!” – they certainly weren’t wrong, but it was a slo-mo explosion. I’ve always been curious to see how good these comics really were, having previously only read Miller from Ronin onwards. The 33 issues on which he worked, between 1979 and ’83, can be found collected in the three volumes of Daredevil: Visionaries: Frank Miller.

Daredevil 158-167, Marvel — 1.5/5

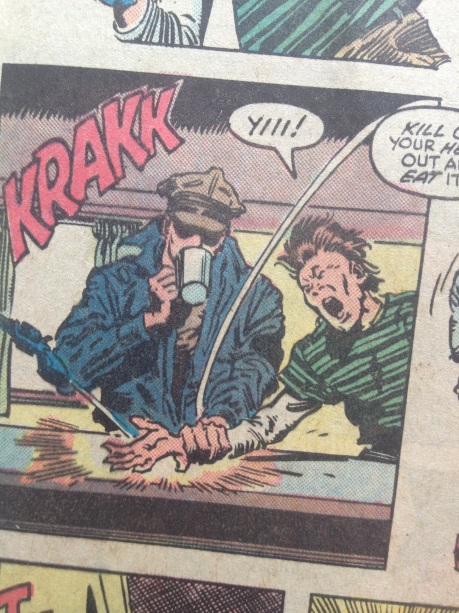

For me, the hackneyed old-school writing by Roger McKenzie and the somewhat formal artwork by a Frank Miller either yet to be given the freedom to run with his own style or not yet having found it, makes reading this initial run a bit of a chore. It’s only interesting as a reference point for the work that would follow.

Daredevil 168-178, Marvel — 2.5/5

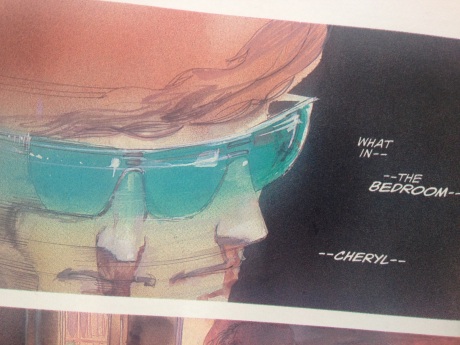

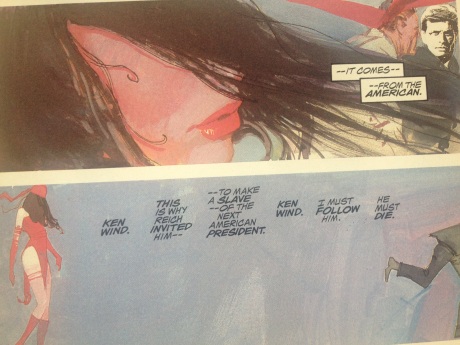

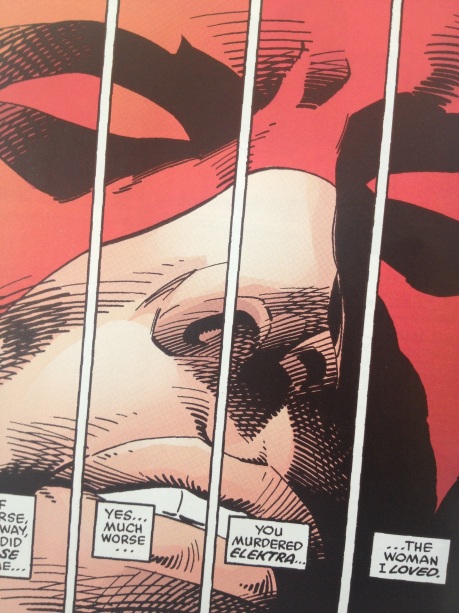

Once Miller and Klaus Janson had proved themselves to Marvel they were allowed to flex their muscles a bit more and you can sense the shift as they gradually turned Daredevil into a smarter, more relevant title. With Miller now taking over writing duties (after threatening to quit over dissatisfaction with McKenzie’s scripts) there was a noticeable increase in depth to the characterisations and the first thing that he did was to introduce a new character, conceived to act as a counterpoint to Daredevil, the strong and tragic Elektra. Allegedly, Daredevil became one of the most widely read titles at the time amongst female readers, no doubt due to Miller providing a relatable and liberated heroine who answered to no-one. Elektra had skills and vulnerabilities that made her an equal to Daredevil, and her introduction created a dynamic that remains one of the most memorable in Marvel’s history; the pages in which they both appear are tense and indeed electric and Miller knew to ration these moments for maximum effect. But it’s not all good: the Bullseye and Kingpin storylines still struggle with ham-fisted dialogue and constant exposition; the use of thought balloons to explain every action is tedious; some stories move at such a rapid pace that they don’t provide any time for the characters to meaningfully reflect or make you care what’s happening; the art is inconsistent, sometimes inventive and kinetic, other times lacking fluidity or finesse; perhaps worst of all, Daredevil is just too self-righteous a goody two-shoes to make you want to root for him and yet, aside from Elektra, there aren’t any antagonists with enough charisma to inspire a switch in allegiance. Perhaps I’d overlook these problems if I’d originally read these issues when I was younger and they were now filtered through the lens of nostalgia, but I imagine Miller would be the first to acknowledge that he was learning on the job. There was still some way for Daredevil to go; you can sense that Miller and Janson were finding ways to reinvent the title and it must have been tricky trying to steer it into darker territory without frightening the traditionalists.

Daredevil 179-191, Marvel — 4.5/5

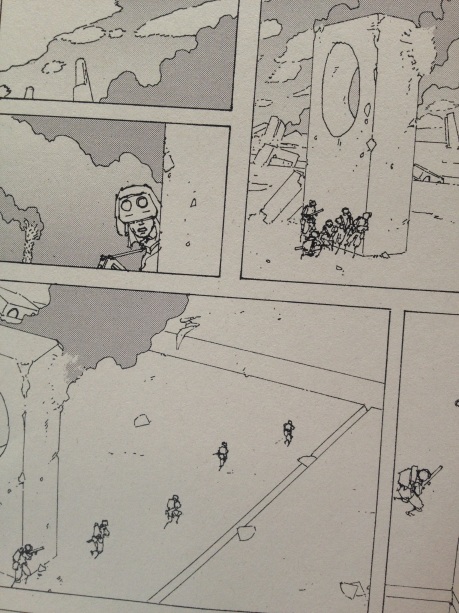

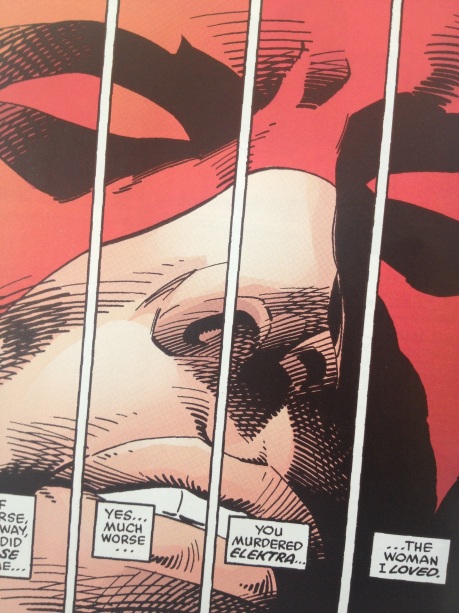

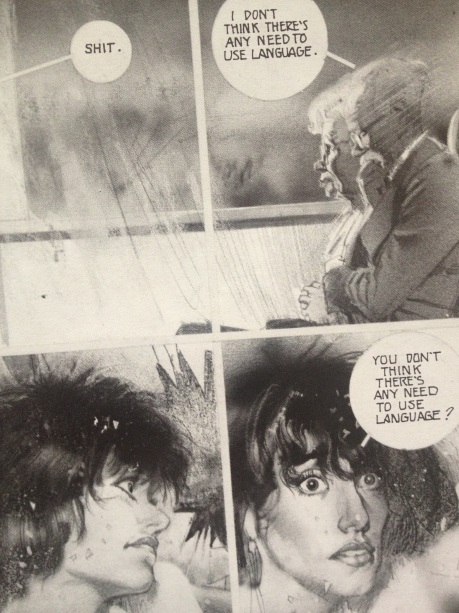

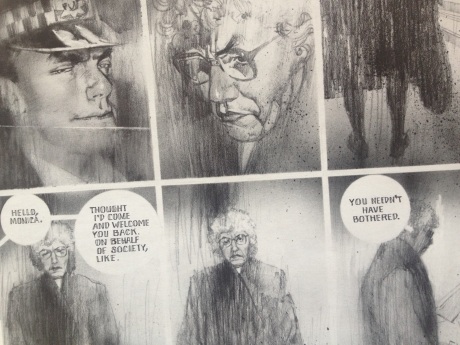

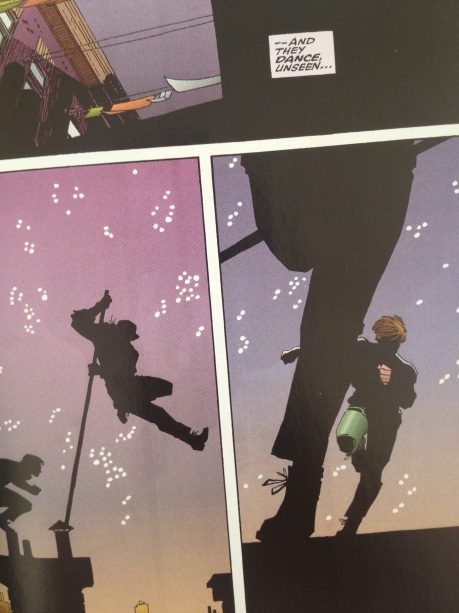

But they got there. From issue 179, Janson took over the colouring from Glynis Wein and the team of Miller and Janson really began to gel. However, it was when Janson started doing the pencilling as well from issue 185, using only the roughest of story layouts from Miller as a guide, that I think the art truly broke free from the rigidity of what had gone before. Larger, more iconic panels with less reliance on text gave the pages so much more power. It’s actually really surprising to me that the visually strongest issues were the ones were Miller took a back seat. Janson was very economical with both line and composition and the lack of distractions meant that the fast paced action was more impactful. Of course, none of this would matter if the scripts were stiff or patronising to the reader but Miller really began to nail it. There is an emphasis on introspection and soul-searching, not just from Daredevil but amongst almost all the supporting characters that makes each story feel crucial to the development of the series. Bullseye was at last given a powerful storyline and issue 181 is incredible and rightly celebrated as the best ever Daredevil issue. Seeds for future plots were sown in intriguing ways and Miller injected some great moments of humour to prevent the series from becoming over-wrought. Miller also started to narrate individual issues from one character’s point of view, giving the reader greater insights into their motivations. Daredevil himself, interestingly, became a poor excuse for a role-model during this final run (for example, his treatment and manipulation of his girlfriend is shameful, and his selfish pursuit of Elektra puts his friends and allies in danger) but ironically, it’s these widening cracks in his previously unimpeachable persona which make him a much more engaging and realistic hero. And it’s the emphasis on reality that was probably Miller’s most important innovation in Daredevil, effectively giving birth to a whole new generation of writers who began placing superheroes in believable worlds, a style obviously still used today. It’s surprising that Miller left Daredevil just as it had reached such heights but presumably he was being offered opportunities to do anything he wanted and he embraced them. You can understand how, fresh from turning the title into such a commercial and creative success, fans were so hyped about his next projects, the Wolverine mini-series and the futuristic samurai epic, Ronin.

MS